Stuck in the middle of clowns and jokers

What should investors do in a dysfunctional and mismanaged world?

Clowns to the left of me, jokers to the right.

Here I am, stuck in the middle with you.

"Stuck in the Middle With You", by Stealers Wheels (Gerry Rafferty), 1972.

…..

Most developed country governments and key institutions appear to be run by clowns and jokers these days. At least when it comes to fiscal and financial policies.

Such situations used to be the preserve of shaky emerging markets and assorted banana republics. But, on their current trajectories, it now applies to most "rich" countries. They are now submerging markets, as I like to call them.

Included within that bag are the USA, Canada, the UK, most of continental Western and Southern Europe, and arguably even Japan.

Of those, the USA and Canada are in the structurally least weak positions, given their large endowments of natural resources. However, the US also has the heavy burden of its huge military spending.

It gives me no pleasure to highlight this situation. But I'm coming from a relatively informed position. That is, given that I live in Buenos Aires, I'm in the belly of a country that was rich in the past, but made itself relatively poor. That was simply through bad policies, applied repeatedly over many decades (see here for more).

Under President Javier Milei, major efforts are being made to turn around Argentina's fortunes. But Argentina's past of decline appears increasingly likely to be prologue for much of the current rich world. Things are not looking good.

At some point in all the debt-sodden countries - perhaps soon - there will be big recessions. It's just a fact of life. Tax receipts will fall, fiscal deficits will become even larger, and governments will have to borrow even more money.

As happened repeatedly since 2008, it's likely that those countries will resort again to central bank money printing (QE) to fund at least part of those deficits. That's in an attempt to keep the government gravy trains on track, and the bond market shows on the road.

But the situation could be approaching a cliff edge in many countries.

First of all, public debts are so huge these days that they could reach a tipping point, whatever governments try to do. If bondholders panic and dump their holdings, then all bets are off.

Second, money printing is obviously inflationary, meaning that currencies could be devalued even more. Many currencies could head down at once, meaning there aren't big moves in relative exchange rates. But they would still lose buying power in the real world, and inflict damage to investor portfolios.

When push comes to shove, desperate governments do desperate things. These include capital controls, such as preventing money going overseas or banning the ownership of certain assets. Or financial repression, such as forcing people to own government bonds (e.g. within tax-advantaged pension accounts). Or confiscation, such as levying high asset / wealth taxes, or seizing assets outright.

The US government banned gold ownership between 1933 and 1974. Here in Argentina, the Peronist government confiscated (sorry... "re-nationalised") private pension funds in 2009, rolling them into the public pension funds in order to "protect" them from the global financial crisis. To cite just two examples.

A reader wrote to me recently expressing concerns about the fiscal situation in the UK and world at large. Too many countries have excessive debts and fiscal deficits, long-dated bond yields are rising, and taxes are already high.

Yet clownish governments, and the jokers that advise them, are doing little or nothing to control bloated public spending and waste. That's despite it being the only way out of the current mess, and very obviously so.

What is the answer for investors? How are we supposed to protect our capital, in the event of one or more sovereign financial crises?

By sovereign crises I mean meltdowns in currency and bond markets. But they typically provoke major sell-offs in stock markets as well. For examples, look up 1997's Asian Crisis, the 1998 Russian Crisis, Argentina's Crisis in 2001/2002, and so on.

The question of how to position investments in such a fiscally precarious world is something I'm constantly wrestling with. There's no obvious safe haven, or strategy that covers all eventualities.

I genuinely think that this is the most complicated investment landscape that's occurred during my lifetime (established in 1972), and certainly in the 32 years since I turned up as a fresh-faced, cheap-suited graduate trainee at a London investment bank.

Yes, it's even more challenging than the run up to the Global Financial Crisis which began in early 2007, with stock markets reaching their nadir in early 2009.

Beware of bonds

Twenty years ago, when government debts were sustainable, the answer to investor angst was easy. Split your money between stocks and bonds, such as the typical 60/40 portfolio. The idea was that if stocks fell hard then bonds would rise. Easy.

But it's much harder now. Personally, I don't want large exposure to the bonds of bankrupt governments with a taste for money printing. I certainly don't want the risk of owning longer-dated bonds that mature in 10, 20, or 30 years. I'm not even convinced by anything with more than 5 years to maturity.

Bitcoin isn't as safe as many believe

Some people think the answer is to own a lot of Bitcoin, since it has limited supply and can't be confiscated. Correct on the first point, but only partially correct on the second one.

If large governments - say all the members of the G7 and EU - get together one day and decide to ban cryptocurrencies, then Bitcoin and the rest would become virtually worthless. Prices would collapse, because no bank, broker or mainstream business would be able to handle them, on pain of being fined heavily or shut down by the authorities.

At which point, owning Bitcoin would be like owning a gold bar that had been dropped into the Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean. Still your property in theory. But pretty much useless and worthless.

As the fiscal pressures continue to mount, such moves by governments become more and more likely. If there are runs on fiat currencies - the dollar, pound, euro, yen etc. - then governments will act to protect themselves. The current US administration may be pro-crypto for now. But that could change, and quickly.

In any case, up until now crypto has been highly correlated with high-growth / tech stocks. The latter tend to be richly priced these days, and would almost certainly collapse if there is some sort of crisis, or even just a recession. Thus, there's a pretty good chance that Bitcoin would follow them down.

Given Bitcoin's huge rise, and large volatility, it's difficult to show a long-term chart that compares it with tech stocks. It makes it look like tech stocks have barely budged, whereas they've actually marched higher.

But here is Bitcoin over the last year indexed against the QQQ ETF, which tracks the NASDAQ 100 index. The point is that both lines tend to rise or fall at similar times. And Bitcoin tends to rise or fall by far larger percentage amounts than the NASDAQ 100.

When it comes to crypto, by all means own some of it. Just don't go overboard. I doubt it would be a haven in a crisis.

What else is there?

Having ruled out longer-dated bonds, and expressed reasons to be cautious about Bitcoin (and definitely its lesser crypto brethren), what are we left with? How do we protect ourselves in an uncertain world?

What we're left with are physical real estate, cash deposits (or cash-like investments), commodities, gold and general stocks.

Real estate

Real estate can be a good wealth preserver in the ultra-long run. This probably explains why Argentines are fanatical about it, in a country with repeated financial crises, high inflation, few credible alternatives, and a very weak currency in the past.

But property prices will also plummet during crises. And buildings or land are highly illiquid assets. The costs (fees and taxes) can be high, both when buying and selling (e.g. capital gains tax). And most places will levy annual property taxes too, which have to be added to any maintenance costs.

So it's only worth buying real estate as a wealth preserver if you plan to own it for many decades, and won't need to sell it to spend the capital any time soon. Given the capital gains taxes levied when it's eventually sold - which are predominantly a tax on inflation - the economics are poor unless there's rental income too (which, of course, is also taxed along the way).

Also note that rental incomes can collapse in real terms in very high inflation environments, as happened recently in high-inflation Argentina (pre-Milei). That's due to the time lag between currencies devaluing and contractual rents being adjusted upwards for inflation.

Cash / near cash

As for cash, we know that fiat currencies lose buying power over time, it's just a question of how fast. And an individual country's currency could devalue substantially in a short period of time, in a crisis. Say, 10-20% in current developed countries within weeks. Perhaps more in later episodes, if they stick with their self-inflicted bankruptcy policies.

But even in a crisis, most of the time the currency will plunge by less than the stock or bond markets that are priced in that currency. So holding cash will still provide firepower to scoop up stock market bargains once the dust has settled, in the hope of making any losses back as prices recover.

By "cash", I mean cash deposits at a bank or broker, as well as investments in short-dated (less than 2-year maturity) government bills and bonds, such as US treasuries or UK gilts. Short-dated inflation-linked bonds are also an option, especially if an investor ends up having a chunky holding for many years, and assuming that governments don't default on the inflation protection.

Cash holdings can also be diversified across currencies, particularly into those of countries with a stronger fiscal position. However, it may not be possible to have Swiss francs deposits, for example, where you live. But you can probably find a short-dated Swiss bond fund as a substitute. The yield will be rubbish, but at least the currency should be relatively stable and strong, unless Switzerland joins the fiscal circus too.

Another place to consider is Norway, and its krone. That country has a gigantic sovereign wealth fund (around $1.8 trillion) and a small population (about 5.6 million). This effectively makes it the richest country in the world, on a per capita basis. The sovereign wealth fund is worth over $321,000 per Norwegian man, woman or child.

Just be aware that the krone often moves in a similar direction to oil and gas prices. Which isn't logical given the strength of the fiscal position, but is just a fact of life. The krone has been weak in recent years, for no genuinely good reason. So arguably it's currently cheap.

In any case, although the sovereign wealth fund would lose a lot of value if global (mainly US) stocks crash, since it's about three-quarters invested in stocks, Norway itself is extremely unlikely to become insolvent and have a sovereign crisis, in my estimation.

Commodities (including silver)

Turning to commodities, or the stocks of commodity producers (miners and drillers), they have the benefit of being / owning real assets that can't be inflated away. However, individual commodity prices are volatile and unpredictable, and affected heavily by economic conditions that influence demand.

Many commodity prices could collapse if major economies get into trouble one day. What's more, geopolitical blow-ups (if, say, China moves on Taiwan) could mean sanctions are imposed, closing off markets to commodity producers.

In short, if you're tempted to buy commodities as a hedge against financial uncertainty and devalued currencies, it's probably best to be extremely diversified. Both in terms of what's produced and where it's produced.

Personally, I include silver within the commodities basket. It's very distinct from gold. Although silver often rockets during the late stages of gold bull markets, it's much more of an industrial metal, with a lot of demand coming from electronics. Which means its price is exposed to economic downturns.

This leaves gold and stocks.

Gold

Personally, I don't see gold as money. If you're a "gold bug", please don't write to me to dispute that. I've heard all the arguments many, many times. Gold was used as money in the past, but it isn't now. We can both like gold, but disagree on this point.

The closest we can get in terms of still thinking about gold as money is that it's used as a low-risk reserve asset by central banks. That's especially by those seeking to diversify away from holdings of US treasury bonds. Such institutions have been big gold buyers in recent years.

My own view is that owning gold as a private investor primarily has two characteristics.

First, gold investors are stockpiling a commodity that's mainly used in jewellery production. As such, it's a bet on long-term wealth accumulation in populous countries such as China and India. Those two trade positions for being the biggest buyers of physical gold in the world. Wealthier people buy more gold jewellery, hence demand for gold is on a rising secular trend.

Second, gold is a crisis hedge. When investors panic about inflation, or when sovereign crises happen, gold will tend to be in high demand as a safe haven. It then does its job of preserving wealth. Personally, I had a very high allocation going into and through the Global Financial Crisis that began in 2007. And I've always maintained a decent allocation since, albeit fluctuating along the way.

Stocks are surprisingly resilient (but with price volatility)

Finally, we get to stocks. Perhaps surprisingly, I think stocks will come through most crises strongly, at least on a medium- to long-term view. Think of the bounce after the Global Financial Crisis, which was by far the largest crisis to hit developed countries ever (apart from World Wars, especially for the losing sides).

Even in Argentina, which has suffered a series of major economic crises in past decades, a pitiful currency, and a stagnant economy, owning stocks has been a good long-term wealth preserver. Yes, really!

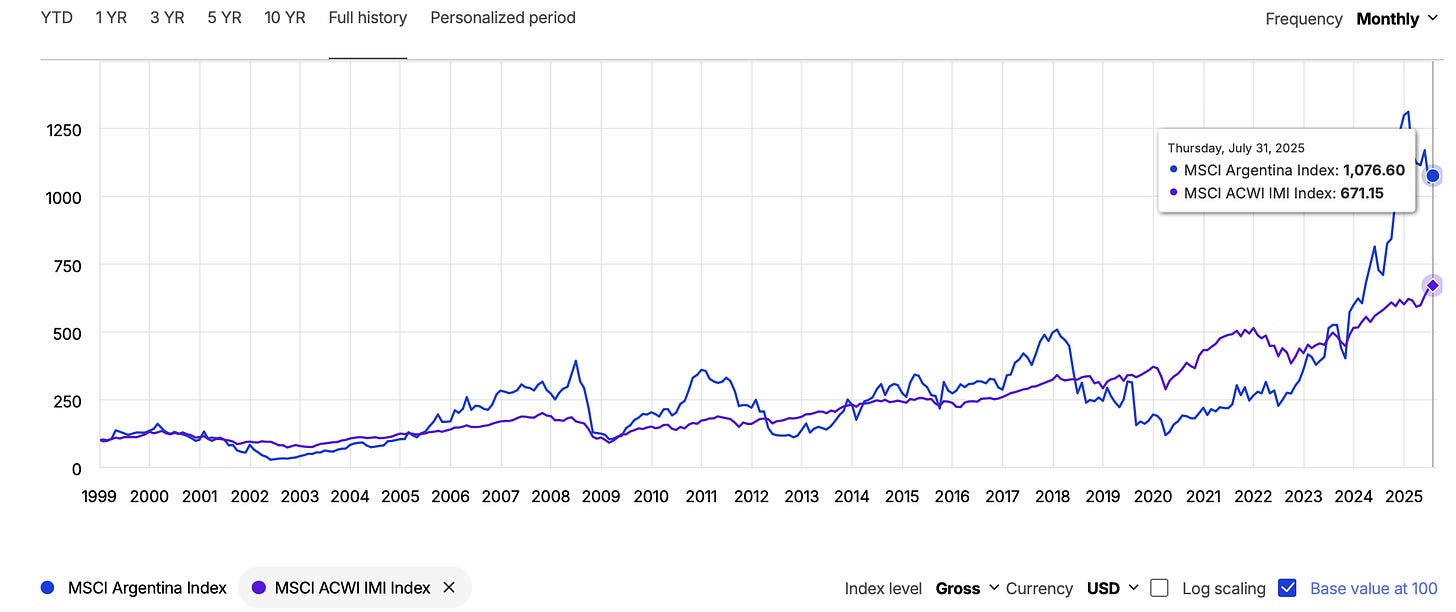

Argentina is the blue line in the following chart from 31 December 1998 to 31 July 2025. It shows total returns (i.e. including re-invested dividends) of the MSCI Argentina index, measured in US dollars. That's set against the diversified MSCI All-Country World Index (ACWI) in purple, albeit currently weighted 65% to the US, given the lofty levels of that market.

Source: MSCI

Amazingly, the Argentina index outperformed the AWCI index over that period. The compound return over those 26 years and 7 months works out at 9.4% a year, measured in US dollars.

That's pretty amazing really, given all that's gone on. Not least, the Argentine peso was pegged 1:1 to the US dollar until January 2002. It then crashed about two-thirds during the 2002 debt default. With one dollar now buying 1,334 pesos, the latter has lost more than 99.9% of its relative value since early 2002.

Now, I'm not saying that was an easy ride. There were monster drawdowns along the way, as Argentina lurched from crises (2000-2002, 2008-2009, 2011-2012, 2018-2020) to moments of over-excitement (2008, 2011, 2017, 2024). And nobody wants to have to wait 27 years to see a payoff.

But it does show that stocks are good long-term wealth preservers, even in countries that are fiscal basket cases. That's largely because companies adjust their prices over time, to keep up with inflation. The skill is to avoid the weak companies that go bust, usually because they can't afford their debts, or are unable to refinance them when they come due.

It's also noteworthy that those investors with the fortitude to invest in Argentina at the crisis lows (2002, 2009, 2012/13, 2020) made huge profits during the recovery periods. But that took plenty of courage, given the highly uncertain political backdrop at those times.

But if similar crises start to strike in other places, investors should look out for opportunities to deploy their cash holdings, with appropriate caution. Crises are scary, but they usually pass. And nowhere in the developed world is anywhere near as fiscally bad as Argentina has been over the past quarter of a century. Well, not yet at least. It's all relative!

I call such investment opportunities "crisis vacations". It was a phrase invented by a friend of mine to refer to cheap holidays in countries that had recently undergone difficulties, such as currency collapses. I just extended it to the investment world.

With stocks: be highly selective and diversify aggressively

Anyway, we should turn back to how to mitigate the growing risks of crises in advance of them actually happening, when it comes to stocks. My view is that it's crucial to be highly selective and to diversify aggressively.

In terms of being highly selective, I mean sticking to stocks of the best companies, and trying to buy them at attractive prices. The best companies tend to have high market shares, strong and persistent sources of demand for their products or services, and strong balance sheets (cash rich, or low / no net debt).

Ways to diversify a stock portfolio include the following:

By the country stock market where stocks are listed. (Note: this is often different to where the company is headquartered, or even where it makes the bulk of its profits.) If all the stocks you own are listed in the same country, then they're likely to all fall at once if the index is hit with a big sell-off.

By types of business (industry sectors). Make sure that what you own is sufficiently spread across a broad range of different business activities.

By size of company: micro, small, medium, large and mega caps. Different groups go in and out of favour at different times.

Between high-growth companies and deep value / high dividend yield companies, and everything in between (e.g. GARP stocks, or growth at a reasonable price). Each will tend to be in and out of favour at different times.

Expanding on high-growth: with 26% a year compound growth, sales or profits will double in three years. At 15% a year, the doubling time is five years. Either will make up for a big fall in market valuation ratios (P/E etc.), provided investors didn't significantly overpay in the first place, and are patient.

Expanding on deep-value / high dividend yield: these are already out of favour, so the pessimism is already baked into the price, relatively speaking. And high dividend yields offset any price falls, especially on a multi-year view. Also, as the dividend cash accumulates it can be re-invested in new bargains that appear after stock markets fall sharply.

By geographical location of the sources of sales revenues and profits.

I'll expand on that last point, since it's something that I very rarely or never hear people talk about. But it's something that I've been focused on heavily this year, for my own portfolio.

That's because of the elevated and rising risks in so many countries these days, as more and more governments progressively lose fiscal control.

Since there's plenty of risk in most places, it's more important than ever to make sure that portfolio companies make their money across a broad spread of countries. They could all go wrong at once. But it's less likely the more there are.