Market musings: 2023's best and worst stock markets

Plus: the US debt bomb, Chinese woes, recession risks, inflation latest and more

In this update:

The best and worst stock markets of 2023

Is China in trouble?

Can the US really avoid recession? Can anyone?

The US debt bomb: a sovereign downgrade and some worrying figures

Falling debt-to-GDP ratios in Europe, but not the UK

Inflation latest: July's US CPI

Markets deliver a cheap time to visit a fascinating Asian country

In case you missed it, don't forget to check out the latest chapter of my investment book, "Getting a Better Class of Enemy - Money, Markets and Manias". Chapter 3 was sent to paid readers on Wednesday. It takes a look at the advantages and disadvantages of being a private investor. It's essential to understand these if you want the best investment outcomes. You can find all the chapters at this link. Chapter 4 will examine profit compounding, including some important insights that most people are not aware of, even if they already understand the basic concepts of compounding.

I do a lot of reading and research for OfWealth, and to guide my own investing. Sometimes, there are relatively quiet periods, and I don't discover much that's new and important. At other times, I discover a lot of things in a short space of time.

In the past few weeks I've found a flurry of things that are notable. The kind of discoveries that really make you sit up and think. Generally, they aren't worthy of a whole article, but they are worth passing on to readers. So today I'll summarise a number of them and what I think they could mean, in what I've called "market musings".

The best and worst stock markets of 2023

Can you guess the best performing country stock index this year, and also over the past 12 months? I certainly wouldn't have managed it before I accidentally noticed something when doing some general research.

It's certainly not the USA. Not even close. In fact it's not a developed market at all, having been downgraded to emerging market status a number of years ago. Nor is it found in Asia or Latin America.

The answer really surprised me when I notice it. Drum roll please...

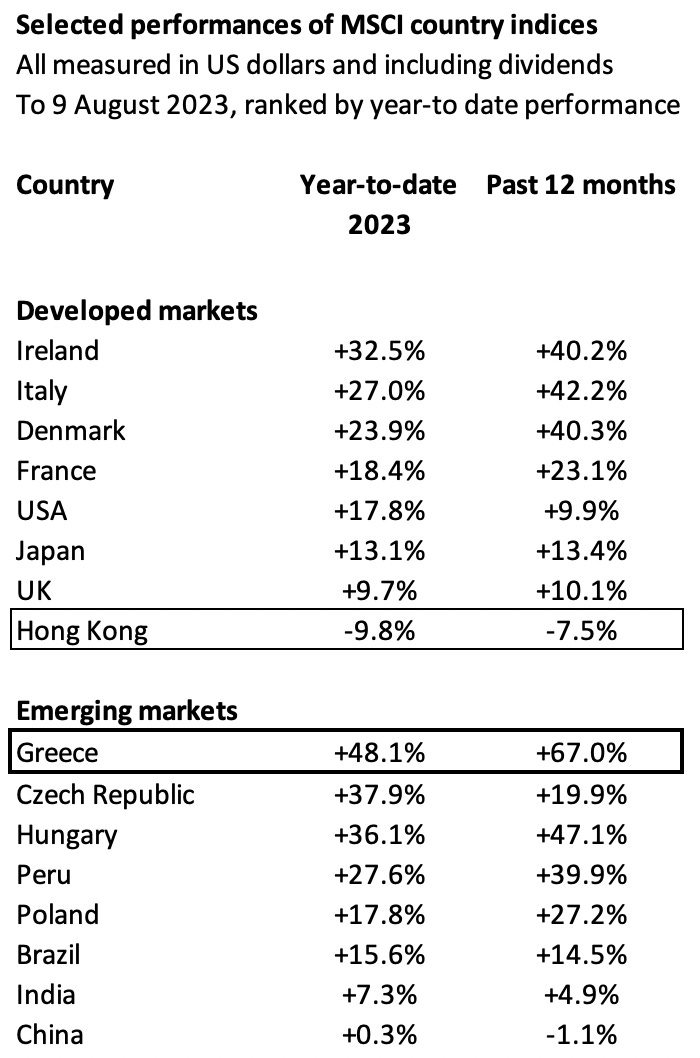

In fact, the best performing country stock index in recent times has been Greece. Up to 9 August, the MSCI Greece index was up 48% year-to-date, and up 67% over the previous 12 months. That's including dividends, and measured in US dollar terms so that we're comparing apples with apples against other countries.

It's not just Greek islands such as Rhodes or Corfu that have been on fire recently (started by arsonists, in case you were wondering... as reported to me by friends that visited both islands at the time). Greek stocks have been on fire too.

(There was a little clue in the photo at the top, which shows a statue of Alexander the Great.)

Below is a summary I put together of selected countries. It includes the best performers among the developed and emerging markets, plus a handful of other major markets in each block (US, UK, Japan, India, Brazil), and the worst performers (Hong Kong and China respectively).

I wanted to highlight this as it shows that you can never be certain which markets will shoot up or down in the short term. Note how Ireland and Italy are at the top of the developed market section.

Along with Greece, those are three of the "PIIGS" countries where investors are doing very well at the moment (P is for Portugal and S is for Spain). PIIGS was the unkind moniker given to those countries in the wake of the global financial crisis, when their economies imploded. It just shows that nothing is forever, and fortunes can turn around.

It's also interesting to see stocks leap in Eastern European countries such as Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, not least given their proximity to the Ukrainian war zone.

Incidentally, the table doesn't show the absolute worst performing market. That honour goes to Kenya, a frontier market in Africa. It's down 29% year-to-date and 42% over the past 12 months. Zimbabwe was the next worst. But such places are pretty much inaccessible for most investors, except the locals, so it's not worth spending time working out what's going on.

Note how Hong Kong and China fill the bottom spots in each block shown. Which brings me on to the next issue...

Is China in trouble?

Personally, I think that China has become a place that foreign investors should avoid these days. Unpredictable political interference in business has increased in recent years, and there's the ever-present possibility that President Xi Jinping will gear up the People's Liberation Army and move on Taiwan at some point. Not least since reuniting China would secure his legacy in the pantheon of Chinese leaders.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, foreign investors in Russia effectively lost the lot due to Western sanctions. China could one day turn out the same way. It's also prudent to avoid stocks of multi-national corporations with a large proportion of their business based in China. Those with Russian businesses mostly took big asset write-downs and profit hits last year.

Even avoiding investing in China, it still pays to watch what's going on there, since it's huge economy that has a big influence on global markets. Examples include demand for commodities and whether Chinese manufactured goods are rising or falling in price, which has inflationary or deflationary consequences when they're exported around the world.

Unlike most other major economies, China's has not rebounded strongly as the pandemic faded and strict lockdown policies were relaxed. I'll admit that this has surprised me.

Inflation never took off there, unlike in the West, and the country has just reported that consumer price inflation for the past year turned slightly negative, which is to say China has a whiff of deflation (albeit modest for now).

If this isn't just a blip, and deflation becomes entrenched, it could lead to all sorts of financial difficulties in China. Debt defaults could spiral, the economy stagnate, banks get into trouble and so forth. It's something to watch.

Separately, I read today that Chinese youth unemployment (ages 16 to 24 years old) is now at 21%, and that's up from 13% in mid-2018. Needless to say, having a lot of unemployed youths around is a recipe for social unrest, which is something the Chinese Communist Party is terrified of.

Let's hope this combination of a weak Chinese economy and spiralling youth unemployment isn't the catalyst for Xi Jinping to launch a Taiwanese "adventure". After all, what better political distraction than a nationalist war? What easier way to keep young adults occupied than conscripting them into the military and thinning their numbers in combat?

Can the US really avoid a recession? Can anyone?

Meanwhile, we're meant to believe that the US will sail through current conditions, achieve an "immaculate soft landing" (as I saw it described), and thus avoid recession.

Aside from economic pronouncements from public officials, this week I saw a research report from Goldman Sachs, the "vampire squid" of investment banks. They're forecasting US real GDP growth of 2.1% this year, 1.7% next year and 1.9% a year in each of 2025 and 2026.

Look, this could be right. But it certainly seems to be more than a tad optimistic. We're in an ongoing interest rate shock, where the Federal Reserve's policy rate (the Fed Funds rate) has risen from 0.08% in February 2022 to the current 5.33%.

That follows a prolonged period of ultra-low rates for most of the period since January 2009, in the thick of the Global Financial Crisis. As such, loads of individual and corporate borrowers, as well as leveraged investors, will be neck deep in debt, and suddenly faced with much higher interest expenses as debts mature and are re-financed at far higher interest rates.

Of course, it's not just the US that faces such issues. Large parts of Europe are in a similar boat, as is Japan. Can they really glide through without a recession, given the huge debt loads and sudden spike in borrowing costs?

Maybe I'm missing something here, but it just seems highly unlikely that nothing will go badly wrong. I suspect we'll find out quite soon.

Which brings me on to the festering pile of filth known as government debts...

The US debt bomb: a sovereign downgrade and some worrying figures

Believe it or not, the US federal government debt isn't as extreme as is usually reported. Although that doesn't mean that there isn't a big problem with US government finances.

The headline debt figure is $32.3 trillion, but $7.8 trillion relates to "intra-governmental" debt balances, which are largely simply accounting entries. The bulk of that $7.8 trillion relates to various state pension programmes, such as Social Security or various schemes for public sector employees.

That reason that that $7.8 trillion is just an accounting entry is that it represents the historical difference between past cash contributions into the programmes (money in) less past payments made to beneficiaries (money out). The net cash has already gone into central government coffers and been spent, meaning there are no "funds" as such. But in any case, most other countries don't report this sort of thing at all.

Thus the actual current "debt", in terms of money directly borrowed by the US government that must be repaid at maturity, was $24.5 trillion at the end of June. This is referred to as "Marketable Securities", since it's in the form of US treasury bills, notes and bonds issued in the past and tradeable in securities markets.

Of that $24.5 trillion, the US Federal Reserve (central bank) still holds $5.0 trillion, which it bought using the money creation process known as Quantitative Easing (QE). In other words, the Fed has effectively funded 20% of the accumulated historical government fiscal deficits, albeit with a bit of smoke and mirrors, by funnelling the money through markets rather than handing it directly to the Treasury department.

But if the Fed hadn't done this, then the government would have had to find an additional $5 trillion from private investors, which surely would have meant bond yields would be higher. It's a supply and demand thing.

On Tuesday 1 August, the US government's sovereign credit rating was downgraded from AAA (the best) to AA+ (a notch lower) by Fitch, one of the three main credit rating agencies. Back in 2011, S&P did the same. This only leaves Moody's awarding the top rating to the US.

The facts of the US's fiscal situation haven't changed. But Fitch's action served to concentrate the minds of the investing world, as well as provoking lots of indignation from government types.

The essential problems are five-fold:

The US federal fiscal deficit was $1.4 trillion last year and is expected to jump to $1.7 trillion this year, meaning the government will have to borrow that much new money. The new borrowing will be at market yields, which currently range from 4% to 5.5% a year, depending on the maturity of the bonds.

Existing US treasury debt maturities are relatively short, with a weighted average of about six years (for comparison, the UK's average time to gilt maturity is a much healthier 15 years). Even worse, I did some digging and discovered that $7.5 trillion of that debt is set to expire in the twelve months from the end of June 2023. That's a massive 31% of the $24.5 trillion of total treasuries in issue. Much of the maturing debt was issued years ago with much lower coupon rates than current market yields, meaning it will have to be refinanced at higher coupon rates, adding to the annual interest bill.

The Federal Reserve is running down its bond holdings to the tune of $80 billion a month, or $960 billion a year. This is reverse QE, known as Quantitative Tightening (QT). Part of that's included within the $7.5 trillion maturing over the coming year, but part involves bond sales into the market. Either way, it means that private sector investor demand will have to soak it all up.

When the US went through its periodic debt-ceiling debacle in May, the US Treasury department couldn't borrow new money, so it had to run down its cash reserves. These will have to be rebuilt, adding perhaps another half to one trillion dollars to new debt issuance.

The annual interest bill has already rocketed to close to $1 trillion a year, up from only around $550 billion in 2020. That's a staggering jump in a short time.

All this points to a further leap in the interest cost of all this debt, as it keeps piling up. I've got some more number crunching to do, since the raw data comes from a spreadsheet that's over 800 lines long, and that’s not exactly user friendly. (It also wasn't easy to find. I wonder why!)

But my current guesstimate is that the interest bill could jump by another $200 billion a year over the next 12 months, taking it to around $1.2 trillion annually.

Unless US governments - now and in future - get a grip on this, it's clear that things could spiral out of control. Getting a grip means cutting spending or raising taxes, and vote-seeking politicians don’t like to do either. Maybe they'll resort to printing money again, stoking inflation once more.

Either way, an eventual crisis of some sort is my baseline expectation, meaning substantially higher bond yields and/or a dollar devaluation. As for the timing? I don't know. But the unsustainable can't be sustained forever.

Of course, it's not just the US that's in this mess. The US is just the most important financial market. Many other developed countries have dug themselves into similarly deep debt holes.

It's worth noting that this leaves them in a weak position to confront future crises, whether of the economic, viral or military kinds. In the face of all this, it seems prudent to own some gold as a crisis hedge.

Falling debt-to-GDP ratios in Europe, but not the UK

One upside of the recent inflationary surge in Europe is that quite a few countries have seen their government debt-to-GDP ratios fall somewhat, although they still remain too high in many cases.

For example, Greece's debt has fallen from above 200% of GDP to close to 140% (this may partially explain the stock market surge).

Meanwhile, Ireland is getting close to just 40% debt-to-GDP ratio, having been above 120% back in 2013.

But there's a big European outlier, namely the United Kingdom. There, the government debt burden keeps climbing, and is now above 100% of GDP. Part of the problem is that about a quarter of the debt in index-linked, meaning the amount to be repaid at maturity grows with inflation. Apparently, the glorious Bank of England didn't think of this when it unleashed its giant spurt of QE during the pandemic.

And then there are the ongoing UK fiscal deficits on top, despite the highest tax burden since the 1940s, relative to GDP. Someday, something's gotta give...

Inflation latest: July's US CPI

July's US consumer price inflation figures have just been released. CPI crept up from 3.0% in the year to June to 3.2% in the year to July. Meanwhile, the core measure that excludes volatile food and energy edged down to 4.7%, from 4.8% in the year to June. Two thirds of the increase relates to "shelter" (i.e. housing, not umbrellas).

This shows that US inflation hasn't yet been fully tamed, which implies no immediate cuts to interest rates.

As for the UK, the July CPI data will be released on 16 August. It stood at a still high 7.9% in the year to June. It will be interesting to see whether and how much it drops.

Markets deliver a cheap time to visit a fascinating Asian country

The Japanese yen has been markedly weak in recent times. It's down 27% against the US dollar since January 2021.

Some people think this is an investment opportunity, and we should be finding ways to bet on a yen recovery. Maybe, maybe not. Personally, I'm not a fan of currency speculation. It's a tough area to get right.

Also, this bout of weakness may be telling us something more profound about Japan. After all, it's a country with an excruciatingly high government debt burden (about 240% of GDP), and a rapidly ageing and shrinking population. Perhaps Japan has reached a point of no return with its finances? Only time will tell.

Anyway, a good friend of mine just came back from spending seven months living there with his Japanese wife. Over a recent lunch of steak and red wine (what else?), he mentioned that Japanese prices seemed pretty cheap at the moment. Decades of ultra-low inflation, or outright deflation at times, combined with the recent currency weakness are to thank for this.

I've been to Japan in the past, when I lived in Hong Kong in the early 2000s. I went to Tokyo many times for business, and once for a holiday, also taking in Kyoto. One of the highlights was spending a night in a ryokan, or traditional guest house. It had been in the same family for many hundreds of years (800?). We wore traditional robes, experienced a tea ceremony in the garden, bathed in a small wooden box and slept (very well) on tatami mats. (This was in the year 1 P.K. of my personal calendar, or one year Pre-Kids.)

I'd love to have had more time to travel around that fascinating country. But I now live on the other side of the world, down here in Argentina (the polar opposite in many other respects as well). For a fella from England, experiencing Japan is truly like stepping into another world. That being a far more technologically advanced world, but still with unique and strong cultural traditions. And sensational food that goes far beyond sushi.

Have you ever wanted to visit Japan? Perhaps you've been in the past but would like to return? Anyway, if you fancy a bargain, now could be a great time to go. Just a suggestion.

Who said studying markets can't have side benefits?

As for investing in Japan? I find it hard to be enthusiastic.

Until next time,

Rob Marstrand

ofwealth@substack.com

The editorial content of OfWealth is for general information only and does not constitute investment advice. It is not intended to be relied upon by individual readers in making (or not making) specific investment decisions. Appropriate independent advice should be obtained before making any such decision.